The 1984 version is a classic and there is now an updated version of A Field Guide to American Houses:

Architecture buffs, decorators, historians and anyone who studies the built environment will have Virginia Savage McAlester’s encyclopedic update of her 1984 book “A Field Guide to American Houses,” (Alfred A Knopf, 2013) on their wish lists.

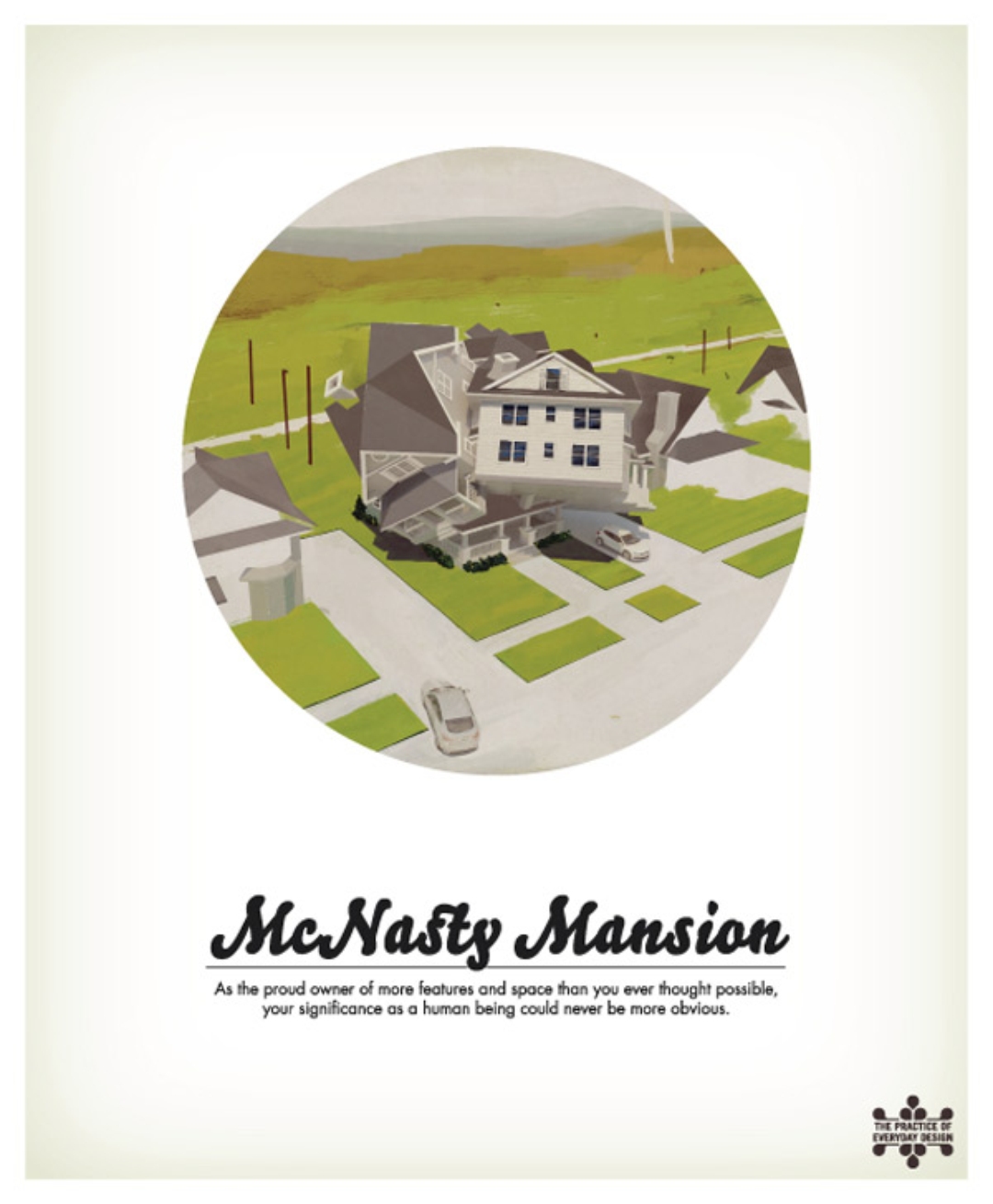

For example: For those who think “prairie palace” and “McMansion” are merely envious epithets for “house bigger than mine,” the author explores the 1980s birth of the Millenium Mansion style and explores the reasons for the wide criticisms (“These complicated roofs can be thought of as crowns, or, more satirically, as the Future Roofers of America Relief Act.”)

For fans of modern ranches, Savage McAlester breaks them down into submovements with different roots. For lovers of historic homes, this is a rich trove of not just details, but reasons for them.

And for those seeking a homeplace that makes sense, the new chapter on neighborhoods is nothing less than essential.

It is hard to find another source that combines the technical features of different styles of American housing architecture as well as good summaries of each architectural movement.It can be hard to keep track of all the different exterior parts that are associated with different architectural styles – keeping your Italianate from your Georgian to your Colonial straight – and this book has helpful diagrams and descriptions.

I’m looking forward to seeing the section on McMansions. If I remember correctly, the 1984 version had a section on more postmodern or eclectic housing styles and McMansions would have likely fallen into that category. But, a reference book like this has the ability to shape understandings of McMansions for years to come.