As many riders know from painful experience, crossing rails embedded in the street is a treacherous undertaking on a bike. There are at least 100,000 at-grade rail crossings in the U.S., not counting city trams and streetcars (which are also notorious for taking down cyclists). But it’s tough to gather data on how many crashes they cause because so few are communicated to the authorities. “The work I looked at, we saw people getting hauled off on ambulances and other things, but very, very few police crash reports,” says Cherry. “There’s a lot of rail infrastructure throughout Tennessee, and I can only imagine how many unreported crashes are occurring statewide or even nationwide.”

That’s part of what motivated Cherry and company to conduct what they call the nation’s first “empirical analysis of rail-grade crossings and single-bicycle crashes.” To them, the problem wasn’t with the cyclists. It was with the roadway design and the fact nobody knows, scientifically speaking, the best way to bike over railroad tracks….

Most experienced riders know the ideal way to do it: As the folks at Bicycling say, cross at a 90-degree angle. That’s the “gold standard” many infrastructure designers strive for. But in cases when the crossing has gaps running in different directions, it might be best to pedal through at 45 degrees. Of course, all this is more complicated when metal tracks are wet, a situation that can turn even a savvy cyclist into a hollering missile directed fast into the pavement…

After pondering a 90-degree crossing that would cost $200,000, partly due to the route being near a river and needing retaining walls, the city and the railroad company settled on a cheaper, roughly 60-degree “jughandle” detour on the side of the street where people were tumbling into traffic. “The total cost was $5,000 for all of that, which is unbelievable, really,” Cherry says. “This has been years in the making, with probably hundreds of crashes there, and it took $5,000 worth of in-house crew time and materials.” (The city later made the path on the other side, located on a greenway, angled to about 60 degrees.)

In addition to bicycles, at-grade crossings are notoriously dangerous for cars and pedestrians. All would do well to pay extra attention when crossing these, even if they are familiar or rarely involve trains. For example, there are several crossings I can think of within a ten mile radius that involve either extra bumpiness, steep approaches, or multiple train lines crossed at once.

While the solution above for bicyclists seems pretty simple, the long-term goal of reducing the number of such crossings is an expensive proposition. It is costly to build bridges and underpasses since in addition to the typical costs of building a bridge or underpass, a solution requires using more land (I recall a proposal to build an overpass in downtown Wheaton that would have obliterated a good portion of the downtown just to provide the necessary ramps) and it can be expensive to construct something while still allowing traffic through (even if roads are closed, trains have a much harder time finding alternative routes).

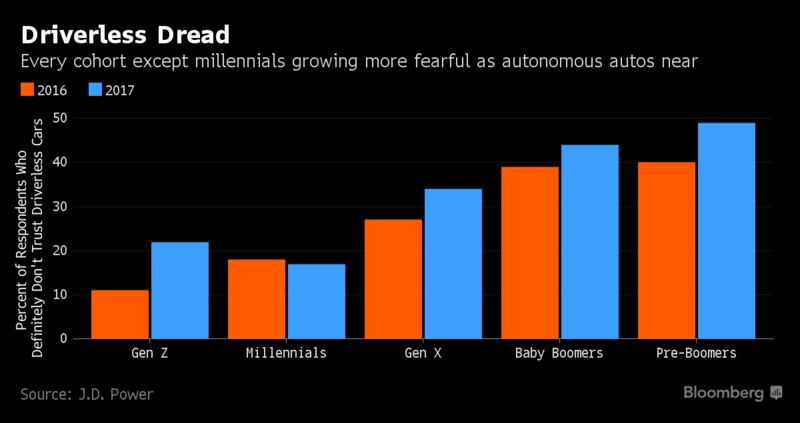

Consumers will only become comfortable with driverless cars after they ride in them, Mary Barra, the chief executive officer of

Consumers will only become comfortable with driverless cars after they ride in them, Mary Barra, the chief executive officer of