This article discusses a cool tool that removes highways on the map so you can see what else is using that space:

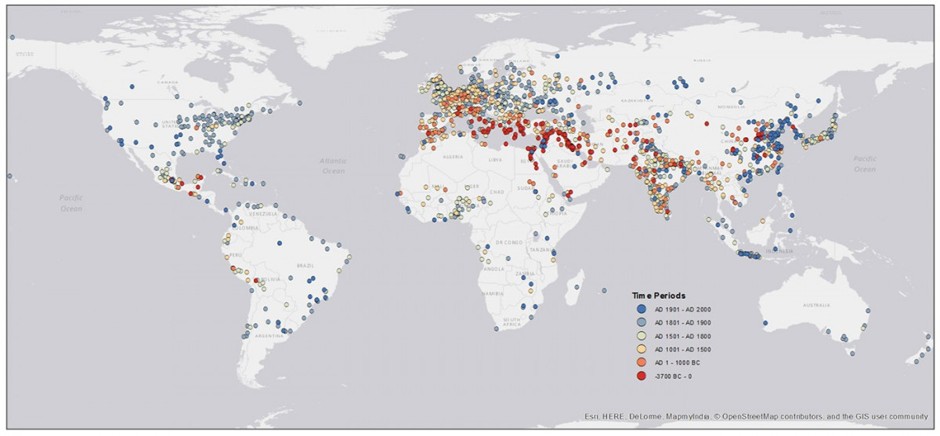

In true public-spirited manner, the map is built from an OpenStreetMap, with tags identifying highways, off-ramps, and exits to make the roads vanish or reappear. However, Sisson didn’t set out on a nihilistic quest to annihilate all highways—he just wanted to look underneath them.

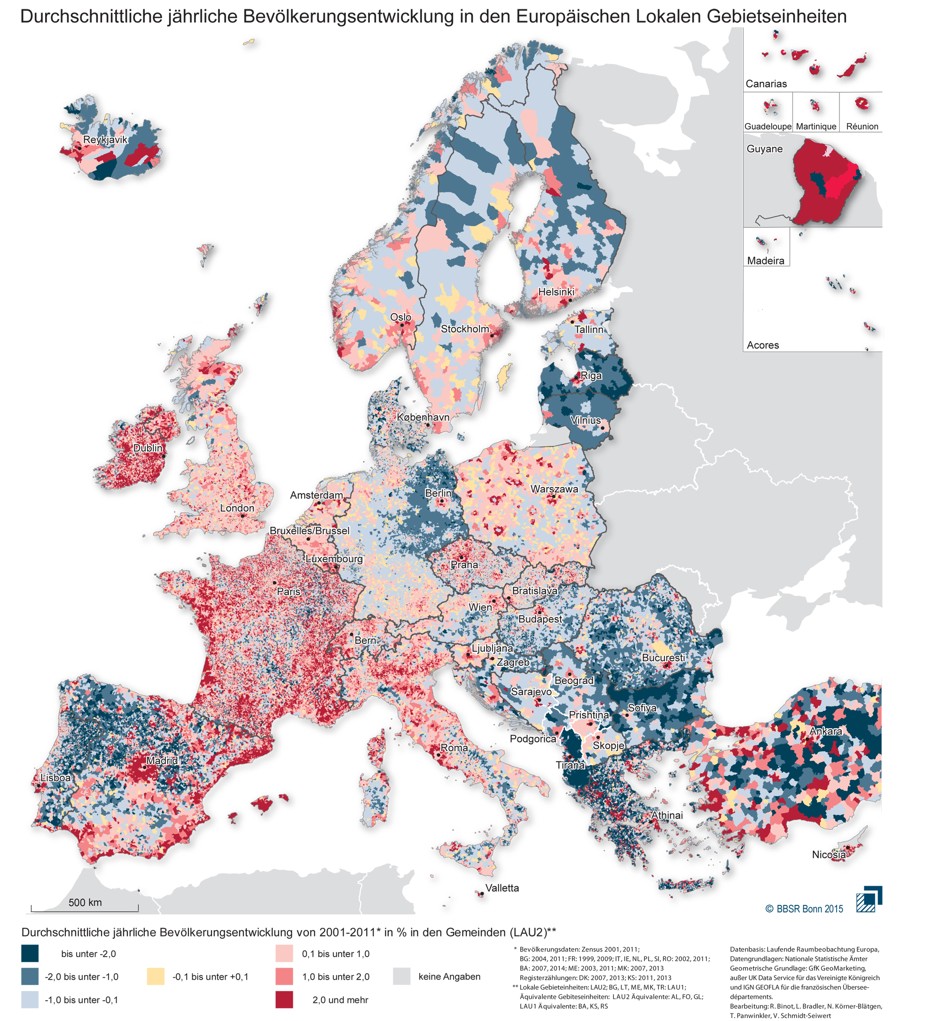

I wish this went one step further: when the highway is removed from the map, could we see what was there before? Urban highways have famously altered numerous neighborhoods – whether the highway that was later replaced by the Big Dig in Boston or the fight between Jane Jacobs and activists in Manhattan and Robert Moses to avoid a new highway or the Dan Ryan in Chicago separating black and white neighborhoods – yet those neighborhoods mostly disappear. The highway seems permanent even though most have only been around for 50-70 years. Of course, it would be really difficult to project what those spaces might look like today if the highway had not been constructed but it would still be nice to be able to peel back the layers. Actually, this wouldn’t be a bad idea for many city locations: what if Google Maps had a timeline component where you could set it to 1950 and see what there then (particularly if images could be incorporated) or even earlier?