This story tracks Mark Zuckerberg’s language about community and the purpose of Facebook. There has been a recent change:

But when 2017 arrived, Zuckerberg immediately began talking about Facebook “building community.” In February, he wrote a massive post detailing his vision to “develop the social infrastructure to give people the power to build a global community that works for all of us.”

We now know that sometime in late 2016, Mark Zuckerberg directed some new questions at his employees. The company had noticed that there was a special subset of Facebook users, about 100 million of them. These were people who had joined “meaningful communities” on the service, which he defined as groups that “quickly become the most important part of your social-network experience and an integral part of your real-world support structure.”..

This marks the first mention of “meaningful communities” from Mark Zuckerberg. In the past, he’d talked about “our” community, “safe” community, and the “global” community, of course. But this was different. Meaning is not as easy to measure as what people click on (or at least most people don’t think it is)…

But the route to a “sense of purpose for everyone is by building community.” This community would be global because “the great arc of human history bends toward people coming together in ever greater numbers—from tribes to cities to nations—to achieve things we couldn’t on our own.”

I could imagine several possible reactions to this new message:

- Cynicism. How can Facebook be trusted if they are a company and their primary goal is to make money? Community sounds good but but perhaps that is what is customers want right now.

- Hope. Facebook began in the minds of college students and now has billions of users. This has all happened very quickly and alongside a number of social media options. While traditional institutions (particularly those related to the nation state) seem to struggle in uniting people, Facebook and other options offer new opportunities.

- Indifference. Many will just continue to use Facebook without much thought of what the company is really doing or trying to figure out what they can really get out of Facebook and other platforms. They just like having connections that they did not used to have.

Given that the messages on connecting people and community has changed in the past, it will be interesting to see how they evolve in the future. In particular, if Zuckerberg wants to get more involved in politics, how will these ideas change?

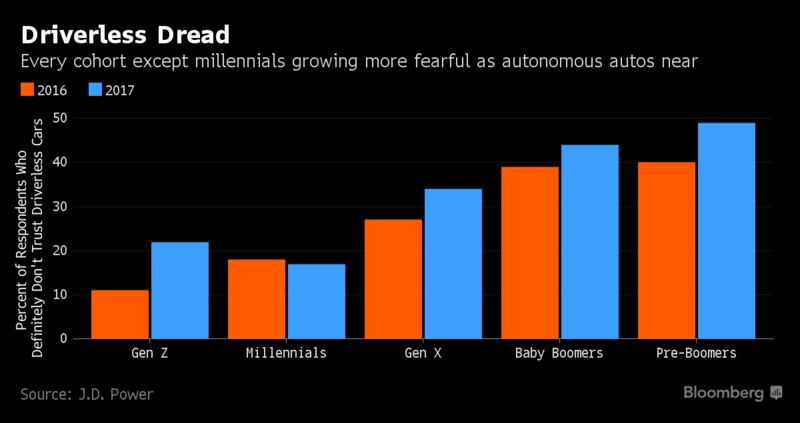

Consumers will only become comfortable with driverless cars after they ride in them, Mary Barra, the chief executive officer of

Consumers will only become comfortable with driverless cars after they ride in them, Mary Barra, the chief executive officer of